The New Air Monitor Has Real-Time Virus Detection Capabilities Including COVID-19, Influenza, and RSV

The School of Medicine and the McKelvey School of Engineering collaborated to develop a prototype air quality sensor capable of detecting the SARS-CoV-2 virus in its natural habitat, inside buildings. The monitor utilizes a nanobody-based biosensor that is embedded into a wet cyclone-based air sampler. Authorization: Joseph Puthussery

Proof-of-concept device could also monitor for flu, RSV, and other respiratory viruses.

Now that the COVID-19 pandemic’s acute phase has passed, researchers are exploring techniques to conduct real-time virus surveillance in enclosed spaces. Washington University in St. Louis scientists have developed a real-time monitor that can detect any of the SARS-CoV-2 virus subtypes in a room in roughly 5 minutes by combining recent advancements in aerosol sampling technology with an ultrasensitive biosensing technique.

The low-cost proof-of-concept gadget might be used to test for respiratory virus aerosols like influenza and respiratory syncytial virus (RSV) in public locations like schools and hospitals. Today (July 10) in the journal Nature Communications, they report the results of their work on the monitor, which they claim is the most sensitive detector available.

Professor Rajan Chakrabarty of the McKelvey School of Engineering; Joseph Puthussery, a postdoctoral research associate in Chakrabarty’s lab; Professor John Cirrito of the Department of Neurology and Associate Professor Carla Yuede of the Department of Psychiatry at the School of Medicine make up the interdisciplinary research team.

At the present time, “there is nothing that tells us how safe a room is,” Cirrito added. You don’t want to wait five days to find out if you might have been sick after being in a room with a hundred other individuals. The equipment is designed to provide results every 5 minutes, making it possible to determine whether or not a live virus is present.

Micro-immunoelectrode (MIE) biosensors were developed by Cirrito and Yuede to detect amyloid beta as a diagnostic for Alzheimer’s disease; they afterwards pondered whether or not this technology could be used to detect SARS-CoV-2. They contacted Chakrabarty, who put together a group that included Puthussery, an expert in developing sensors to monitor air quality in real time.

Researchers switched out the antibody for one that detects the spike protein in SARS-CoV-2 by using llama nanobodies. This allowed them to use the biosensor to detect coronaviruses instead of amyloid beta. The nanobody was created in the lab at the National Institutes of Health (NIH) by David Brody, MD, PhD, an author on the study and a former faculty member in the Department of Neurology at the School of Medicine. According to the scientists, the nanobody has the advantages of being compact, versatile, and cheap to build.

“The nanobody-based electrochemical approach is faster at detecting the virus because it doesn’t need a reagent or a lot of processing steps,” Yuede explained. According to the authors, “SARS-CoV-2 binds to the nanobodies on the surface, and we can induce oxidation of tyrosines on the surface of the virus using a technique called square wave voltammetry to get a measurement of the amount of virus in the sample.”

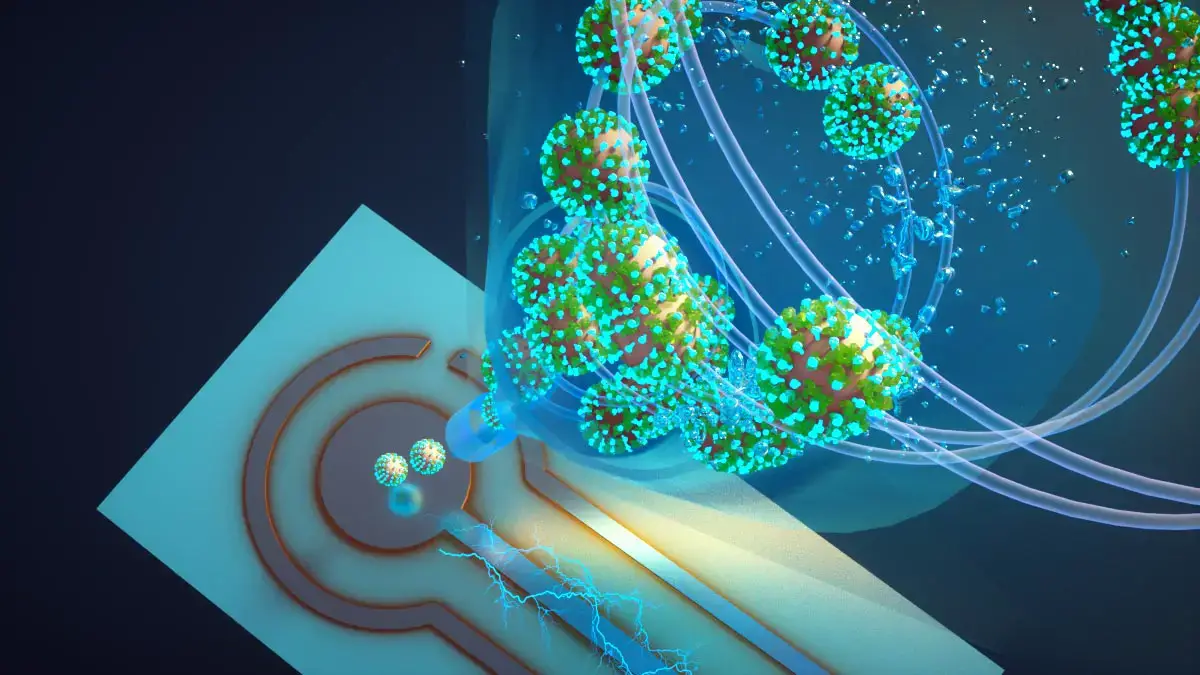

The biosensor was incorporated by Chakrabarty and Puthussery into a wet cyclone-based air sampler. In order to capture the virus aerosols, the sampler uses centrifugal force to mix the incoming air with the fluid lining the walls of the sampler, creating a surface vortex. The fluid is collected by the wet cyclone sampler’s automated pump and then sent on to the biosensor, where the virus may be detected electrochemically in a smooth process.

“The challenge with airborne aerosol detectors is that the level of virus in the indoor air is so diluted that it even pushes toward the limit of detection of polymerase chain reaction (PCR), and is like finding a needle in a haystack,” Chakrabarty said. The wet cyclone’s high flow rate allows it to gather a larger volume of air in under 5 minutes, which contributes to its high viral recovery when compared to commercially available samplers.

According to Puthussery, the team’s monitor has one of the greatest flow rates of any commercially available bioaerosol sampler at around 1,000 liters per minute. It has a small footprint of about 1 foot broad by 10 inches tall, and its LED indicator lights up when a virus is discovered to warn administrators to open windows or otherwise improve ventilation.

The monitor was put through its paces in the homes of two COVID-positive patients. Air samples were taken from the bedrooms and compared to those taken from a virus-free control room using real-time PCR. The virus’s RNA was discovered in the bedroom air samples, but not in the control air samples.

After only a few minutes of sampling, the wet cyclone and biosensor were able to identify different degrees of airborne virus concentrations when SARS-CoV-2 was aerosolized in a laboratory chamber the size of a room.

“We are starting with SARS-CoV-2, but there are plans to also measure influenza, RSV, rhinovirus, and other top pathogens that routinely infect people,” Cirrito added. Complications from staph and strep infections may be measured using the monitor if it were utilized in a hospital setting. The implications for human health could be enormous.